My 1st true difficult airway…. something I hope to never see again, but who am I kidding? It’s my job to be an airway expert… therefore, that only means I will be challenging my skills and will someday encounter that dreaded unintubateable airway.

The patient was a friendly, easy-going gal who was an anesthesiologist’s nightmare. She was coming in for a 3 vessel CABG… she was a known difficult IV access (yes, she came from the floor with an infiltrated 22g IV). She stood proud at 5’3″, 255lb, short chin, small mouth opening, and thick neck. She had had her cath done a couple days prior to her surgery — and yes, the radial artery was used. In addition to her already challenging anatomy, the surgeon requested that her other radial artery be spared for grafting.

I go to meet her in the holding area. She was so nice…friendly… had a positive attitude. These are the patients I love to care for. After updating her H&P and checking her consent, I apprehensively started searching for venous access. 3 PIV sticks..with flash but no luck. 2 attempts with U/S…no luck. Luckily, my a-line went in without any trouble. The attending tried several times for a PIV as well with U/S.. no luck.

We wheeled her back to the OR. She had a rather unchallenging R IJ MAC introducer placement (thank goodness!). Now to go to sleep!

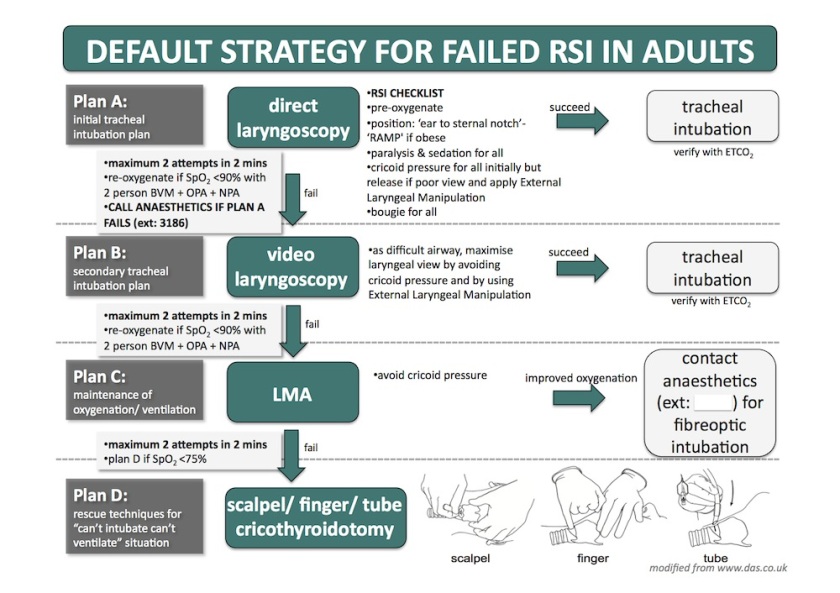

We had a glidescope and bougie handy… knowing this intubation could be difficult. (In retrospect, I would’ve had the fiberoptic cart and an LMA within reach). We pre-oxygenated in reverse T-burg for what seemed like forever. Go time: Prop, sux,… glidescope…. barely saw arytenoids…even with a glidescope!! Small mouth opening kept us from truly getting the styletted tube in her mouth. I took a look for what felt like maybe 5 seconds and could eerily hear the sat probe dwindle down… 100….98……95……92….87….84…. time to mask ventilate!! We 2-hand mask her… a very difficult mask! Oral airway in…still difficult. Reposition, jaw lift,…sats 64…52….39… “Call for help” exclaimed my attending! I called out for an LMA and a bougie and told the surgeons to be on standby for an emergency airway.

Fortunately, we were able to place an LMA #4 and slowly ventilate her back up to 100% sat. By now, there were 3 other anesthesiologists and an anesthesia tech who came to help.

We had an airway, but couldn’t proceed with the surgery with just an LMA…we needed to secure her airway. We switched over to a Fast trach LMA#5…one that would accomodate a 7.0 ETT. We used a fiberoptic scope to look down the LMA. It was difficult to discern the structures. She had a pretty small glottic opening…and after several attempts, we were able to guide the fiberoptic scope down into the trachea and secure a breathing tube for ventilation.

Once the tube was secured… I took a step back and realized this could have been a disaster. However, we initiated all the right things in the difficult airway algorithm and saved this woman’s life. It was incredible.

After her surgery, we delivered her to the SICU, intubated. She was extubated the next morning under the supervision of an anesthesiologist. Everything went well. She recovered well from her CABG and was informed to have “difficult airway” written all over her medical record.

Key points:

-Call for help early

-Always have backup airway devices ready

-Even as a resident, don’t depend on your attendings to bail you out of trouble….b/c someday, that “attending” will be you.

-Reflect at the end of a challenging case