https://pubs.asahq.org/monitor/article/87/7/13/138362/The-Current-and-Future-State-of-Anesthesiology

Tag: anesthesia

Hypoglossal Nerve Stimulators for OSA

UpToDate: Hypoglossal nerve stimulation for adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea. April 2024

StatPearls: Hypoglossal Stimulation Device. July 2023

Things that worked for me:

- ETT, sux (no lingering paralysis secondary to upcoming nerve stimulation)

- Propofol gtt with 12 mcg Precedex in 50cc syringe

- Fentanyl for pain

- HOB 180 degrees away

Compensation for Services

The Full Guide to Physician On-call Pay | Physicians Thrive

Physician Call Compensation Rates: 11 Determining Factors (beckershospitalreview.com)

Anesthesia Stipend Analysis (anesthesiaexperts.com)

Managing Compensation for Anesthesiologists, CRNAs and AAs (beckersasc.com)

28 Statistics on Highest Emergency On-Call Coverage Per Diem Payments (beckershospitalreview.com) –> 2012 data

Hospital Call Stipends : r/anesthesiology (reddit.com)

Anesthesia Management: MGMA: No guarantees for physician on-call pay | Anesthesia Experts –> 2014 post

Locum tenens compensation trends by specialty | 2023 report (locumstory.com)

Understanding Call Pay Compensation Methods – Coker (cokergroup.com)

Developing an Anesthesia Compensation Model That Makes Sense | Change Healthcare

3 Trends Impacting Anesthesia Compensation – ECG Management Consultants

Where do we see anesthesia going as well as reimbursements?

Medicare’s geographic adjustment for a particular physician payment locality is determined using three geographic practice cost indices (GPCI) that correspond to the three components of a Medicare fee–physician work, practice expense, and malpractice expense.

Physician work–the financial value of physicians’ time, skill, and effort that are associated with providing the service.

Practice expense–the costs incurred by physicians in employing office staff, renting office space, and buying supplies and equipment.

Malpractice expense–the premiums paid by physicians for professional liability insurance. Each RVU measures the relative costliness of providing a particular service.

These GPCIs adjust physician fees for variations in physicians’ costs of providing care in different payment localities. Specifically, they raise or lower Medicare fees depending on whether a payment locality’s average cost of operating a physician practice is above or below the national average. CMS is required to review the GPCIs at least every 3 years and, at that time, may update them using more recent data. The major data source used in calculating the GPCIs, the decennial census, provides new data once every 10 years. The GPCIs were last updated in 2005 and CMS is scheduled to review and, if necessary, update them again in 2008. Concerns have been raised in Congress and among stakeholders, including state medical associations, that the geographic boundaries of some payment localities do not accurately address variations in the costs of operating a private medical practice. If they do not, beneficiaries could potentially experience problems accessing physician services.

From https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-GAO-07-466/html/GAOREPORTS-GAO-07-466.htm

More than half of the current physician payment localities had at least one county within them with a large payment difference–that is, there was a payment difference of 5 percent or more between physicians’ costs and Medicare’s geographic adjustment for an area. Overall, there were 447 counties with large payment differences–representing 14 percent of all counties. These counties were located across the United States, but a disproportionate number were located in five states. Specifically, 60 percent of counties with large payment differences were located in California, Georgia, Minnesota, Ohio, and Virginia. Large payment differences occur because many payment localities combine counties with very different costs, which may be attributed to several factors. For example, although substantial population growth has occurred in certain geographic areas, potentially leading to increased costs, CMS has not revised the payment localities to reflect these changes.

From https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-GAO-07-466/html/GAOREPORTS-GAO-07-466.htm

Perhaps insurance company data could be used to help discover discrepancies in cost and apply new findings to these geographic areas.

CMS Physician Fee Schedule — Anesthesia specific

ASA: Anesthesia Payments –> The 33% Problem — AnesthesiaExperts:33% Rule

AnesthesiaExperts: Q&A on the 33% problem

AnesthesiaLLC.com: The Low, Low Anesthesia Conversion Factor

Lawmakers Ask HHS to Review Medicare Rates for Anesthesia Services, Sept 2010

Anesthesia Subsidies from a Hospital’s Perspective

ECG Management Consultants:

AnesthesiaLLC.com: Today’s Anesthesia Economics Coping with New Realities.

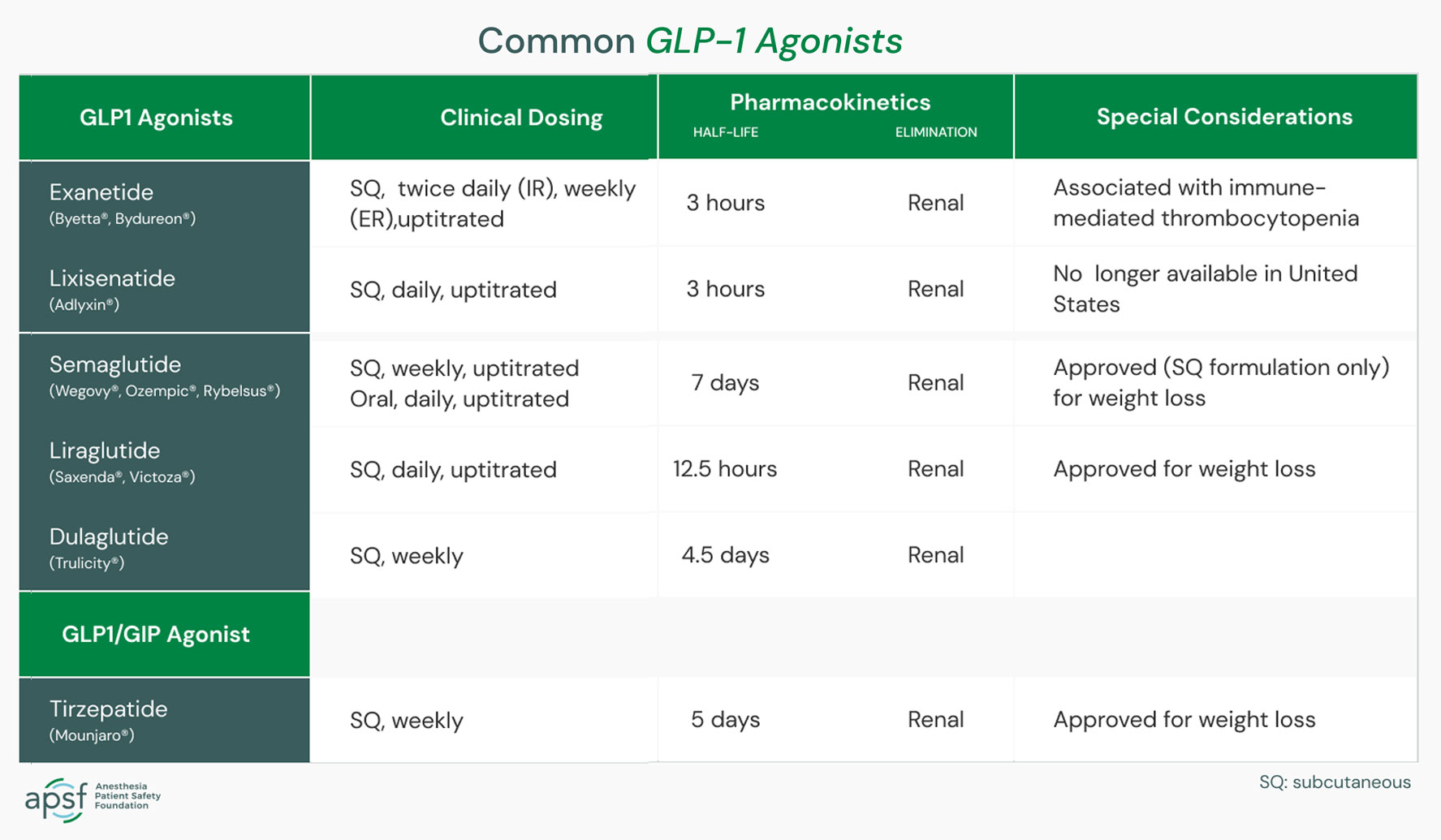

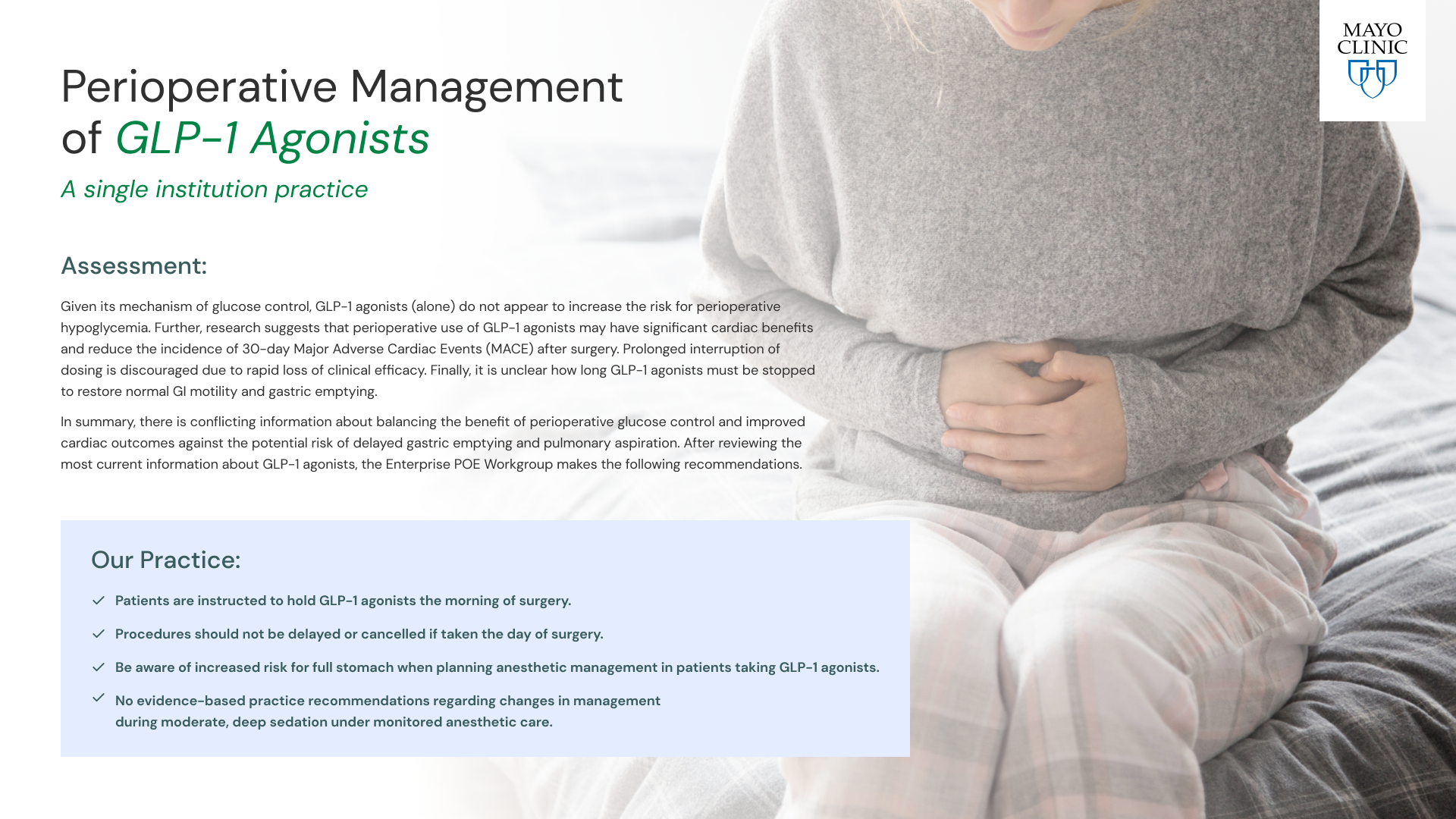

Ozempic and other Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor Agonists

ASA’s Task Force on Preoperative Fasting suggests the following for patients taking GLP-1 agonists for type 2 diabetes or weight loss who are having elective procedures. It is also calling for further research to be done regarding GLP-1 agonist medications and anesthesia.

Day or week prior to the procedure:

- Hold GLP-1 agonists on the day of the procedure/surgery for patients who take the medication daily.

- Hold GLP-1 agonists a week prior to the procedure/surgery for patients who take the medication weekly.

- Consider consulting with an endocrinologist for guidance in patients who are taking GLP-1 agonists for diabetes management to help control their condition and prevent hyperglycemia (high blood sugar).

Day of the procedure:

- Consider delaying the procedure if the patient is experiencing GI symptoms such as severe nausea/vomiting/retching, abdominal bloating or abdominal pain and discuss the concerns of potential risk of regurgitation and aspiration with the proceduralist or surgeon and the patient.

- Continue with the procedure if the patient has no GI symptoms and the GLP-1 agonist medications have been held as advised.

- If the patient has no GI symptoms, but the GLP-1 agonist medications were not held, use precautions based on the assumption the patient has a “full stomach” or consider using ultrasound to evaluate the stomach contents. If the stomach is empty, proceed as usual. If the stomach is full or if the gastric ultrasound is inconclusive or not possible, consider delaying the procedure or proceed using full stomach precautions. Discuss the potential risk of regurgitation and aspiration of gastric contents with the proceduralist or surgeon and the patient.

Full stomach precautions also should be used in patients who need urgent or emergency surgery.

From ASA: Patients Taking Popular Medications for Diabetes and Weight Loss Should Stop Before Elective Surgery, ASA Suggests. June 2023.

NYT: Ozempic, Nov 2022.

TEE Billing during Anesthesia

TEE has been bundled into certain anesthesia services where TEE is necessary for a successful procedure. This basically means the qualified anesthesiologist does not get reimbursed for his or her expertise in guiding placement of a device, monitoring, or generating a report.

CMS Billing and Coding for TEE

MediCal California anesthesias billing

Code 59 If the TEE is performed for diagnostic purposes by the same anesthesiologist who is providing the anesthesia service, modifier 59 should be appended to the TEE code to note that it is distinct and independent from the anesthesia service.

Center for Medicare Services policy that defines reimbursable indications for intraoperative TEE “The interpretation of TEE during surgery is covered only when the surgeon or other physician has requested echocardiography for a specific diagnostic reason (e.g., determination of proper valve placement, assessment of the adequacy of valvuloplasty or revascularization, placement of shunts or other devices, assessment of vascular integrity, or detection of intravascular air). To be a covered service, TEE must include a complete interpretation/report by the performing physician.

Duke TEE Billing Codes

Procedure Coding: When to use modifier 59

AAPC Anesthesia and TEE billing in same procedure

TEE Documentation Requirements Crucial for Anesthesia Billing

TEE Documentation Requirements from AnesthesiaLLC.com

Watchman Reimbursement guide: pg. 11

UnitedHealthcare Anesthesia Billing

Based on our review of the analysis, the most interesting findings include:

ASA Survey Results for Commercial Fees Paid for Anesthesia Services – 2015. ASA Monitor October 2015, Vol. 79, 48–54.

- ■ The national average conversion factor increased from a range of $66.98-$71.79 in 2014 to a range of $69.64-$74.29. Also, the median conversion factor range broadened from $63.88-$69.00 in 2014 to $65.00-$69.00.

- ■ Conversion factors across the country are similar, with the Eastern Region still having the highest mean of $77.96.

- ■ Every region and nearly every contract category had a reported conversion factor high of at least $82.00. The highest conversion factor reported was $195.00.

Blogs

IV Fentanyl while waiting for labor epidural

Anesthesia for Latissimus Dorsi Flap for Breast Reconstruction

What is a latissimus dorsi flap?

Anesthetic Techniques

Anaesthesia for breast surgery. BJA Education, 18(11): 342e348 (2018).

Comparison of local and regional anesthesia modalities in breast surgery: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2021 Sep;72:110274.

Efficacy of regional anesthesia techniques for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing major oncologic breast surgeries: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2022 Apr;69(4):527-549.

Efficacy of erector spinae plane block for analgesia in breast surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2021 Mar;76(3):404-413.

Erector Spinae Plane Block Similar to Paravertebral Block for Perioperative Pain Control in Breast Surgery: A Meta-Analysis Study. Pain Physician. 2021 May;24(3):203-213.

Tranexamic Acid vs. Amicar

** Updated July 2023** Scroll down for update

Over the years, our hospital has been using Amicar… until there was a drug shortage. With that drug shortage came a different drug called tranexamic acid. We’ve been using it for awhile and I can’t seem to tell a difference in coagulation between the two drugs. Let’s break down each one and also discuss cost-effectiveness.

Amicar

Tranexamic Acid

What is it?

Tranexamic acid acts by reversibly blocking the lysine binding sites of plasminogen, thus preventing plasmin activation and, as a result, the lysis of polymerised fibrin.12 Tranexamic acid is frequently utilised to enhance haemostasis, particularly when fibrinolysis contributes to bleeding. In clinical practice, tranexamic acid has been used to treat menorrhagia, trauma-associated bleeding and to prevent perioperative bleeding associated with orthopaedic and cardiac surgery.13–16 Importantly, the use of tranexamic acid is not without adverse effects. Tranexamic acid has been associated with seizures,17 18 as well as concerns of possible increased thromboembolic events, including stroke which to date have not been demonstrated in randomised controlled trials.

Fibrinolysis is the mechanism of clot breakdown and involves a cascade of interactions between zymogens and enzymes that act in concert with clot formation to maintain blood flow.25 During extracorporeal circulation, such as cardiopulmonary bypass used in cardiac surgery, multiplex changes in haemostasis arise that include accelerated thrombin generation, platelet dysfunction and enhanced fibrinolysis.26 Tranexamic acid inhibits fibrinolysis, a putative mechanism of bleeding after cardiopulmonary bypass, by forming a reversible complex with plasminogen.

Dosing:

- Cardiac Surgery

- Tranexamic Acid in Patients Undergoing Coronary-Artery Surgery. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:136-148.

- In summary, we found no evidence that tranexamic acid increases the risk of death and thrombotic complications after coronary-artery surgery. Tranexamic acid was associated with a lower risk of bleeding complications than placebo but also with a higher risk of postoperative seizures.

- Tranexamic acid in cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis (protocol). BMJ Open. 2019; 9(9): e028585.

- Different dose regimes and administration methods of tranexamic acid in cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. BMC Anesthesiology volume 19, Article number: 129 (2019).

- The study used a high-dose regimen, in which either 50 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg of TXA was delivered for each patient. There is a possibility that lower dose of TXA can be equally effective while causing less adverse effects. In fact, TXA plasma concentrations required to suppress fibrinolysis and plasmin-induced platelet activation are merely 10 and 16 μg/ml, respectively [7, 8]. This relatively low plasma concentration can be reached in cardiac surgery when 10 mg/kg of TXA is administered as a bolus then followed by continuous infusion of 1 mg kg/h and 1 mg/kg in CPB [9]. But another potential mechanism of TXA action might be the increase in thrombin formation, which requires concentrations more than 126 μg/ml to be effective [10, 11]. 30 mg/kg of TXA administered as a bolus followed by 16 mg/kg/h and 2 mg/kg in CPB prime solution was able to maintain the plasma concentration above 114 μg/ml [9].

- Optimal Tranexamic Acid Dosing Regimen in Cardiac Surgery: What Are the Missing Pieces? Anesthesiology February 2021, Vol. 134, 143–146.

- Using their model-based meta-analysis, the authors conclude that low-dose tranexamic acid (total dose of 20 mg/kg of actual body weight) provides the best balance between reduction in postoperative blood loss and red blood cell transfusion and the risk of clinical seizure. The use of higher doses would only marginally improve the clinical effect at the cost of an increased risk of seizure.

- Tranexamic Acid Dosing for Cardiac Surgical Patients With Chronic Renal Dysfunction: A New Dosing Regimen. Anesthesia & Analgesia: December 2018 – Volume 127 – Issue 6 – p 1323-1332.

- Low-risk group received a single 50 mg/kg TXA bolus after induction of anesthesia. The high-risk group received Blood Conservation Using Anti-fibrinolytics Trial (BART) TXA regimen, consisting of 30 mg/kg bolus infused over 15 minutes after induction, followed by 16 mg/kg/h infusion until chest closure with a 2 mg/kg load within the pump prime.

- What dose of tranexamic acid is most effective and safe for adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery? Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery, Volume 21, Issue 3, September 2015, Pages 384–388.

- Risk of seizure is dose-dependent, with the greatest risk at higher doses of tranexamic acid. We conclude that, in general, patients with a high risk of bleeding should receive high-dose tranexamic acid, while those at low risk of bleeding should receive low-dose tranexamic acid with consideration given to potential dose-related seizure risk. We recommend the regimens of high-dose (30 mg kg−1 bolus + 16 mg kg−1 h−1 + 2 mg kg−1 priming) and low-dose (10 mg kg−1 bolus + 1 mg kg−1 h−1 + 1 mg kg−1 priming) tranexamic acid, as these are well established in terms of safety profile and have the strongest evidence for efficacy.

- Exposure–Response Relationship of Tranexamic Acid in Cardiac Surgery: A Model-based Meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2021; 134:165–78.

- The exposure value with the low-dose tranexamic acid regimen proposed by Horrow et al. (10 mg/kg followed by 1 mg/kg/h over 12 h) was close to the 80% effective concentration for postoperative blood loss and above the 80% effective concentration for erythrocyte transfusion. Compared to this regimen, a fivefold increase in total dose (100 mg/kg) achieved only a 58 ml (95% credible interval,54 to 65 ml) increment in the reduction of postoperative blood loss, up to 48 h postsurgery, with a decrease in erythrocyte transfusion rate from 46% to 44%.

- Concentrations close to 80% effective concentration can be achieved at the end of surgery with a low-dose regimen administered either as a preoperative bolus plus infusion (10mg/kg followed by 1mg/kg/h) or as a single preoperative loading dose of 20mg/kg (fig. 6). Postoperative administration of tranexamic acid appears unnecessary because tranexamic acid concentrations will decrease but nevertheless remain sufficient (greater than or equal to EC50) up to the end of the drug’s contribution to blood loss reduction (8 h after the start of surgery).

- The type of surgery and the duration of CPB both affected the risk of seizure. Open-chamber surgery resulted in a 5.5-fold increase in the risk of seizure compared to closed-chamber procedures (95% credible interval, 3.2 to 10). Each additional hour of CPB doubled the risk of seizure (2.0;95% credible interval, 1.2 to 3.2).

- Tranexamic Acid in Patients Undergoing Coronary-Artery Surgery. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:136-148.

- Ortho/Spine

- OB

- Trauma

Currently at our hospital (June 2022):

TXA DOSING AND ADMINISTRATION OVERVIEW

| How supplied from Pharmacy | TXA 1000mg/10mL vials Will not provide premade bags like with Amicar; Amicar is a more complex mixture than TXA Will take feedback on this after go-live and reassess |

| Where it will be supplied from Pharmacy | POR-SUR1 Omnicell (in HeartCore Room) Perfusion Tray (will replace aminocaproic acid vials 6/7) |

| Recommended Dosing (see below for evidence) | ~20 mg/kg total dose Can give as: 20 mg/kg x 1, OR 10 mg/kg x 1, followed by 1-2 mg/kg/h* Perfusion may also prime bypass solution with 2 mg/kg x 1* |

| Preparation & Administration | IV push straight drug (1000mg/10mL) from vial AND/OR Mix vial of 1000mg/10mL TXA with 250mL NS for continuous infusion* |

TXA & Amicar ADRs

- SEIZURE RISK with TXA

- TXA has shown dose-dependent increased risk of seizure compared to placebo. (Myles, et al. N Engl J Med 2017)

- TXA may also have an increased risk of post-operative seizures compared to Amicar (Martin, et al. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011)

- Seizure risk may be increased also by duration of prolonged open-chamber surgery based on findings from Zuffery, et al. Anesthesiology 2021.

- Per OR pharmacist at Scripps Mercy, they have not seen an increased incidence of seizures in their patient-population (anecdotally)

- RENAL DYSFUNCTION WITH AMICAR (LOWER RISK WITH TXA)

- In the Martin study, TXA showed a lower risk of post-op renal dysfunction compared to Amicar (Martin, et al. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011)

DOSING EVIDENCE

There are a number of dosing strategies in the literature. What I recommend for maximal safety and efficacy is taken from Zuffery, et al. Anesthesiology 2021 meta-analysis and is practiced at Scripps Mercy.

- ~ 20 mg/kg total dose recommended in this meta-analysis.

- Two dosing strategies they report that were as effective as high-dose but with lower seizure risk than high dose:

- 20 mg/kg preoperative bolus x 1 (taken from Lambert, et al. Can J Anaesth. 1998)

- OR 10 mg/kg preoperative bolus x1, followed by 1 mg/kg/h for up to 12 hours (from Horrow, et al. Anesthesiology. 1995)

UPDATE JULY 2023

Carrie our pharmacist provided some really helpful research and updates:

So really we have two questions here I am seeking to answer with your group: (1) Is TXA best given as a bolus or as an infusion during cardiac surgery, and my other question (2) What is the optimal TXA dosage?

The JAMA 2022 study focuses on the question of dosing, though I believe it also helps answer the question about continuing drips post-op.

In this study, they did a bolus/infusion but only during the surgery.

They performed a randomized double-blind trial of 2 different TXA dosing strategies for adults undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB. They two dosing strategies:

- “High dose”: TXA 30mg/kg bolus followed by 16mg/kg/h during surgery only and 2mg/kg pump prime

- “Low dose”: TXA 10mg/kg bolus followed by 10mg/kg/h during surgery only and 1mg/kg pump prime

Results:

Efficacy: 21.8% of patients in the high-dose group received at least 1 allogeneic RBC transfusion compared to 26.0% in the low-dose group (p=0.004).

Safety: The composite safety endpoint (seizure, kidney dysfunction, thrombotic events, and all-cause mortality) was 17.6% in high-dose vs 16.8% in low-dose (p=0.004 for noninferiority)

I like this infographic on their study and results:

My takeaway on the JAMA study: I’m not sold on the “high dosing” regimen because I’m not overly impressed by their efficacy endpoint. Transfusion of at least 1 PRBC by itself doesn’t say much (in my opinion – let me know what you think!). Transfusion of FFP, platelets, cryo were no different between dosing groups. Chest tube output was not statistically different post-op. Duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU length of stay, and hospital length of stay were not statistically different.

Furthermore, if you comb through their secondary safety endpoints, you can see where TXA “low dose” patients had lower rates of seizures compared to high dose. This was especially true for open chamber surgery.

This doesn’t answer the question you asked about dosing strategy – bolus versus drip. However, they did only run TXA intraoperatively and did NOT give it post-op, which at least supports the idea we don’t need it upon ICU transfer.

I’m in favor of us moving toward the above JAMA “low dose” strategy among our anesthesiologists who are running drips. I think we can actually increase the rate of the infusion and STOP it before patient transfers, because at that point TXA will have already done all the leg work it is going to do.

Okay, so back to the question on bolus versus infusion:

The 2021 Zuffery article from Anesthesiologydoes not really take a stance on how to administer, though they do include a couple articles where the researchers only used bolus dosing (e.g. Lambert et al, who studied 20 mg/kg bolus compared to higher dosing regimens).

I really like their Figure 6, where they show pharmacokinetics and outcomes based on four different TXA regimen simulations. You can see where TXA 20mg/kg bolus (represented with yellow) is pretty similar outcomes and PK-wise to the green 10mg/kg bolus followed by 1mg/kg/h for 12 hours. AKA what you’re doing vs. what most of your colleagues are doing – same outcomes represented in this simulation.

This NEJM RCT from 2017 from Myles, et al studied 50mg/kg and dosed as follows : “30-min loading dose of 12.5 mg/kg with a maintenance infusion of 6.5 mg/kg/hr, and 1 mg/kg added to the CPB prime, will be used” > Infusions again, but intraop only. This study also started with giving 100 mg/kg!! Patients were seizing, so they pulled back 50mg/kg.

My plan:

TXA 20mg/kg over 20 minutes prior to incision + 2mg/kg in pump prime. No infusion.

Is your workplace hazardous to your health??

I found myself on the wrong side of the ether screen earlier this year, having surgery on my left hand to release Dupuytren’s contracture, a genetic gift from my father and (maybe) generations of our Viking forebears. Wondering how long it will take to heal – and when I’ll get some (any?) grip strength back […]

Is your workplace hazardous to your health??